All the news that's fit to tweet

Breaking news is broken, and Twitter looks guilty. I was in New York for a social media summit at the New York Times, surrounded by some of the best and brightest social media journalists and news leaders from around the globe when news of the Boston Marathon bombings was unfolding.

While online current affairs and culture magazine Slate were telling people to go into a self-imposed exile to avoid the “cul-de-sacs and dark alleys of misinformation” contained in the breaking news about Boston on cable television and on Twitter, a panel was hastily put together to examine the main problems of breaking news in 2013, and to call for solutions.

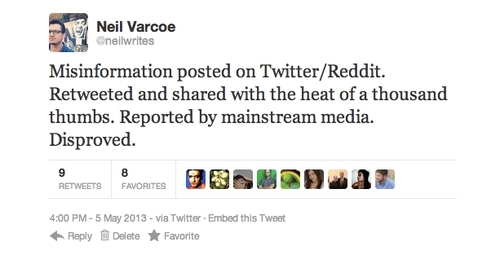

For those of you who accepted the advice from Slate and avoided the swirling vortex of misreporting on traditional and new media, here is a recap in 140 characters or less:

Claire Wardle of Storyful, a news agency that verifies social media content for clients including The New York Times and at my workplace, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), chaired the session. Panellists included Andrew Hawken (Head of Digital at Sky News), Liz Heron (Director of Social Media and Engagement at the Wall Street Journal) and Lisa Tozzi, an editor at the New York Times who directed The Lede blog, which provided real-time coverage of the bombings. Tozzi, it was announced in the days after, will start a new role on May 14 as News Director at Buzzfeed — a prolific social news site more often associated with cat memes than breaking news coverage — another sure sign the traditional media model has been recast.

Intent on making the best use of the specific expertise in the room to provide meaningful solutions, we broke off into small groups to pull apart the critical failures of fact in the reporting of Boston, and the noise in the room rose to a steady hum as passionate media types set the cracks.

A range of solutions were tabled from editable tweets and verification task forces to the attractive but impractical idea of applying a media credit ratings system much like Moody’s or Fitch.

Like sixth graders at their first spelling bee, typically cocksure journalists walked with apprehension to the microphone to announce their conclusions, voices soft with doubt.

While the ideas were sound and will be taken to the relevant social media platforms, some of which were represented in the audience, one idea rose above all others in my mind.

One conference goer swaggered brassily to the microphone and declared: “Don’t tweet unless you have something to say.” This was accompanied by silence, then another elegant solution: “Don’t report rumour or speculation.

Sitting in the newly-created TimesCenter in the shadow of the New York Times, the now famous words that have adorned the front page of the The Grey Lady for some 116 years — “All the news that’s fit to print” — took hold in my ear.

The paper and the media landscape have evolved beyond recognition. One thing that remains true is the need to check the veracity of information to ensure it’s ‘fit’ for publication, which includes Twitter.

If you do not trust the information, then wait. When journalists get it wrong, and they will, they should correct the record, whether by a retraction in the newspaper, an on-air apology, an online update or in the not-too-distant-future an ‘editable tweet.’ Many media organisations both in the United States and here in Australia failed to do any of these in the days that followed the bombings.

When you boil it down, blaming social media for journalists and media organisations getting it wrong is like yelling at the head printer for a mistake carried down from the newsroom floor. And I think we deserve better than that, don’t you?

Would you like to catch up on the conversation from Social Media Summit? Check out my Storify of the best tweets from the conference.